Theory of Operation¶

Density measurements for photography and graphic technology is officially based upon the following standards documents [1]:

ISO 5-1:2009 - Geometry and functional notation

ISO 5-2:2009 - Geometric conditions for transmittance density

ISO 5-3:2009 - Spectral conditions

ISO 5-4:2009 - Geometric conditions for reflection density

Basic Calculations¶

Reflection Density¶

Reflection density is typically defined by the following formula:

\(D_R = -log_{10} R\)

In this formula, “R” is defined as the reflectance factor. That means it is the ratio of light detected by the sensor as reflecting off of the target material, to light that would be detected if the target was a perfectly reflecting and perfectly diffusing material.

In practice, the reflection calculations are based on using two reference measurements to draw a line in logarithmic space. The location of the target measurement along this line then determines its density.

The inputs to this calculation are:

\(V_{target}\): Sensor measurement of the target material

\(V_{hi}\): Sensor measurement of the CAL-HI reference

\(D_{hi}\): Known density of the CAL-HI reference

\(V_{lo}\): Sensor measurement of the CAL-LO reference

\(D_{lo}\): Known density of the CAL-LO reference

First, all the input measurements are converted into logarithmic space:

Then the slope of the line connecting CAL-HI and CAL-LO is determined:

Finally, the measured density is calculated:

Note

An alternative approach would be to use just the CAL-LO properties to determine what a perfect reflection reading would be, then use that value in the original density formula. In theory, this would yield the same answer. In practice however, due to limited density precision of the reference strips, the results would be slightly different. For this reason, the single reference point approach is only viable when using laboratory grade reflectance standards.

Transmission Density¶

Transmission density is typically defined by the following formula:

\(D_T = -log_{10} T\)

In this formula, “T” is defined as the transmittance factor. That means it is the ratio of light detected by the sensor as passing through the target material, to light that would be detected if the path from the light source to the sensor was unobstructed.

In practice, the transmission calculations are based on using two reference measurements to compensate for any sensor error. One is the measurement of an unobstructed light path, while the other is the measurement of a high density reference material.

The inputs to this calculation are:

\(V_{target}\): Sensor measurement of the target material

\(V_{hi}\): Sensor measurement of the CAL-HI reference

\(D_{hi}\): Known density of the CAL-HI reference

\(V_{zero}\): Sensor measurement of an unobstructed light path

First, calculate the measured target and CAL-HI densities relative to the unobstructed light reading:

Then calculate the adjustment factor based on the known density of our CAL-HI reference:

Finally, put these together to calculate the transmission density:

Preparing Readings¶

Before any of the above calculations can be performed, the raw sensor readings must first be converted into a normalized and corrected form. This conversion takes into account a number of sensor properties to arrive at a floating point value that is independent of the sensor’s measurement settings and is corrected for any deviations in the sensor’s response curve.

This process consists of the following steps:

Start with the raw sensor reading and parameters

Convert to basic counts, which factor in gain and integration time

Apply temperature correction, which is based on the ambient temperature inside the sensor head

As the input to each of these steps depends on the output of the previous steps, calibration is performed in the same order that the corrections are applied. All the calibration measurements required for this process are performed as part of device manufacturing, as they typically require conditions, instruments, or materials not provided with the device itself.

Gain Calibration¶

Because of the wide range of light values that need to be measured, the gain setting of the sensor cannot be kept constant across all measurements. Therefore, the current gain setting needs to be factored into any calculations that compare sensor readings.

The datasheet for the sensor does not provide exact values for these gain settings, but rather a range that can be expected.

Setting |

Min |

Typical |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|

0.5x |

0.47 |

0.51 |

0.55 |

1x |

0.96 |

1.03 |

1.11 |

2x |

1.91 |

2.03 |

2.15 |

4x |

3.83 |

4.04 |

4.24 |

8x |

7.92 |

8.24 |

8.57 |

16x |

15.42 |

16.06 |

16.71 |

32x |

30.84 |

32.08 |

33.42 |

64x |

61.24 |

63.68 |

66.32 |

128x |

- |

128 |

- |

256x |

227.84 |

247.04 |

264.96 |

To determine the actual values for these gain settings, or as close to them as we can get, a calibration process is required. This process is mostly automated, triggered by the desktop application. It works by leaving the device unattended with the sensor head held closed by a weight or strap, while a series of independent raw measurements are performed. For the sake of consistency, gain calibration is typically performed at an ambient temperature of approximarely 20°C.

For each adjacent pair of gain settings, the following process is performed:

Determine the appropriate light brightness to get a good reading at the higher gain, without saturation

Measure the light at the lower gain

Meadure the light at the higher gain

Calculate the ratio between these two gains

Between each step there is a cooldown cycle, to ensure consistent readings.

Once these readings are complete, we end up with a table such as this:

Pair |

Ratio |

|---|---|

\(g_1/g_0\) |

2.02896631 |

\(g_2/g_1\) |

1.97246370 |

\(g_3/g_2\) |

1.99469659 |

\(g_4/g_3\) |

1.93522371 |

\(g_5/g_4\) |

1.97304038 |

\(g_6/g_5\) |

1.99064724 |

\(g_7/g_6\) |

1.98492706 |

\(g_8/g_7\) |

2.00797774 |

\(g_9/g_8\) |

1.90163819 |

We then take the highest gain we can measure at full brightness without sensor saturation, set that as the reference gain, and calculate the actual gain table as follows:

Gain |

Setting |

Actual Value |

|---|---|---|

\(g_0\) |

0.5x |

0.517843 |

\(g_1\) |

1x |

1.050686 |

\(g_2\) |

2x |

2.072440 |

\(g_3\) |

4x |

4.133889 |

\(g_4\) |

8x |

8.000000 |

\(g_5\) |

16x |

15.784323 |

\(g_6\) |

32x |

31.421019 |

\(g_7\) |

64x |

62.368431 |

\(g_8\) |

128x |

125.234421 |

\(g_9\) |

256x |

238.150558 |

Converting to Basic Counts¶

Raw sensor readings cannot be compared directly, because there are a number of variables that need to be taken into consideration. The process of incorporating these into the result transforms that result from a raw reading into something referred to as “basic counts.”

The inputs to this conversion are as follows:

\(V_{raw}\): Raw 32-bit integer representing the output of the sensor’s analog-to-digital converter (ADC)

\(A_{time}\): Sensor integration time, in milliseconds [2]

\(A_{gain}\): Sensor gain value, for the active gain setting, as determined above

The conversion itself is then as follows:

Temperature Calibration¶

The behavior of the sensor and the light source is sensitive to the ambient temperature. This effect is minimal in the visual spectrum mode, though it is more pronounced in the UV spectrum mode as shown in Fig. 9. To ensure accuracy of readings across the range of ambient temperatures, a calibration process has been implemented to measure and compensate for this effect. The calibration and compensation is performed in relation to readings from a temperature sensor located inside the sensor head and adjacent to the light sensor.

Fig. 9 Temperature sensitivity of density readings¶

The first step of the calibration process is data collection. The device is placed in a thermal chamber, and is then brought down to a stable starting temperature of approximately 10°C. From this point forward, measurements are collected across a range of light brightness settings to simulate a range of target density measurements. The chamber temperature is then increased and the process repeats.

Overall, it looks something like this:

Wait for temperature to stabilize

Collect visible light measurements, in gain corrected basic counts, across a series of light brightness settings

Collect UV light measurements, in gain corrected basic counts, across a series of light brightness settings

Record the data

Increase chamber temperature by 5°C and repeat

Temperature |

0.00D |

0.30D |

0.60D |

0.90D |

1.20D |

1.50D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12.0 |

80.624400 |

40.527200 |

20.388300 |

10.229900 |

5.085100 |

2.561430 |

16.6 |

80.383200 |

40.376700 |

20.308300 |

10.185900 |

5.103220 |

2.550920 |

21.2 |

80.112600 |

40.276900 |

20.199500 |

10.147100 |

5.077500 |

2.538070 |

26.2 |

79.804600 |

40.188800 |

20.137800 |

10.105900 |

5.067340 |

2.532660 |

31.1 |

79.395500 |

39.878600 |

19.963600 |

10.002500 |

5.015060 |

2.524280 |

35.7 |

79.010600 |

39.749600 |

19.975100 |

10.021300 |

5.017890 |

2.499880 |

40.8 |

78.595700 |

39.542600 |

19.844400 |

9.960600 |

4.988500 |

2.493090 |

Temperature Correction¶

Once the data is collected, the next step is to calculate a set of coefficients that can correct any reading to equivalent values at a reference temperature. The reference temperature being used is whichever dataset is closest to 20°C.

The first step is to iterate over each temperature, and calculate the correction multiplier necessary to make each reading match that of the reference temperature.

Temperature |

0.00D |

0.30D |

0.60D |

0.90D |

1.20D |

1.50D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12.0 |

0.002766 |

0.002691 |

0.004040 |

0.003529 |

0.000650 |

0.003979 |

16.6 |

0.001464 |

0.001075 |

0.002333 |

0.001657 |

0.002194 |

0.002193 |

21.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

26.2 |

-0.001673 |

-0.000951 |

-0.001329 |

-0.001767 |

-0.000870 |

-0.000927 |

31.1 |

-0.003905 |

-0.004316 |

-0.005102 |

-0.006233 |

-0.005374 |

-0.002366 |

35.7 |

-0.006015 |

-0.005723 |

-0.004852 |

-0.005418 |

-0.005129 |

-0.006584 |

40.8 |

-0.008302 |

-0.007991 |

-0.007703 |

-0.008056 |

-0.007680 |

-0.007766 |

These results are then averaged, to give a good common correction value for each temperature.

Temperature |

Average Correction |

|---|---|

12.0 |

0.002942 |

16.6 |

0.001820 |

21.2 |

0.0 |

26.2 |

-0.001253 |

31.1 |

-0.004549 |

35.7 |

-0.005620 |

40.8 |

-0.007916 |

Finally, a second-order polynomial regression is performed to establish a set of coefficients for the relationship between temperature and an appropriate correction value.

Coefficient |

Value |

|---|---|

\(B_0\) |

-0.548861 |

\(B_1\) |

0.070635 |

\(B_2\) |

-0.001488 |

These correction coefficients can then be used to calculate the correction for any temperature reading, which is then applied to the sensor result prior to performing density calculation.

To demonstrate the effect of these corrections, a 5-patch step wedge was measured on a calibrated device at room temperature. The device was then placed in a hot room where this measurement was repeated at regular intervals as the device temperature rose. The change in readings was then graphed, both with and without temperature corrections applied.

Fig. 10 Temperature correction experiment¶

The results are shown in Fig. 10. There is a relatively modest improvement in the visual spectrum readings, and a dramatic improvement in the UV spectrum readings.

Sensor Head Design¶

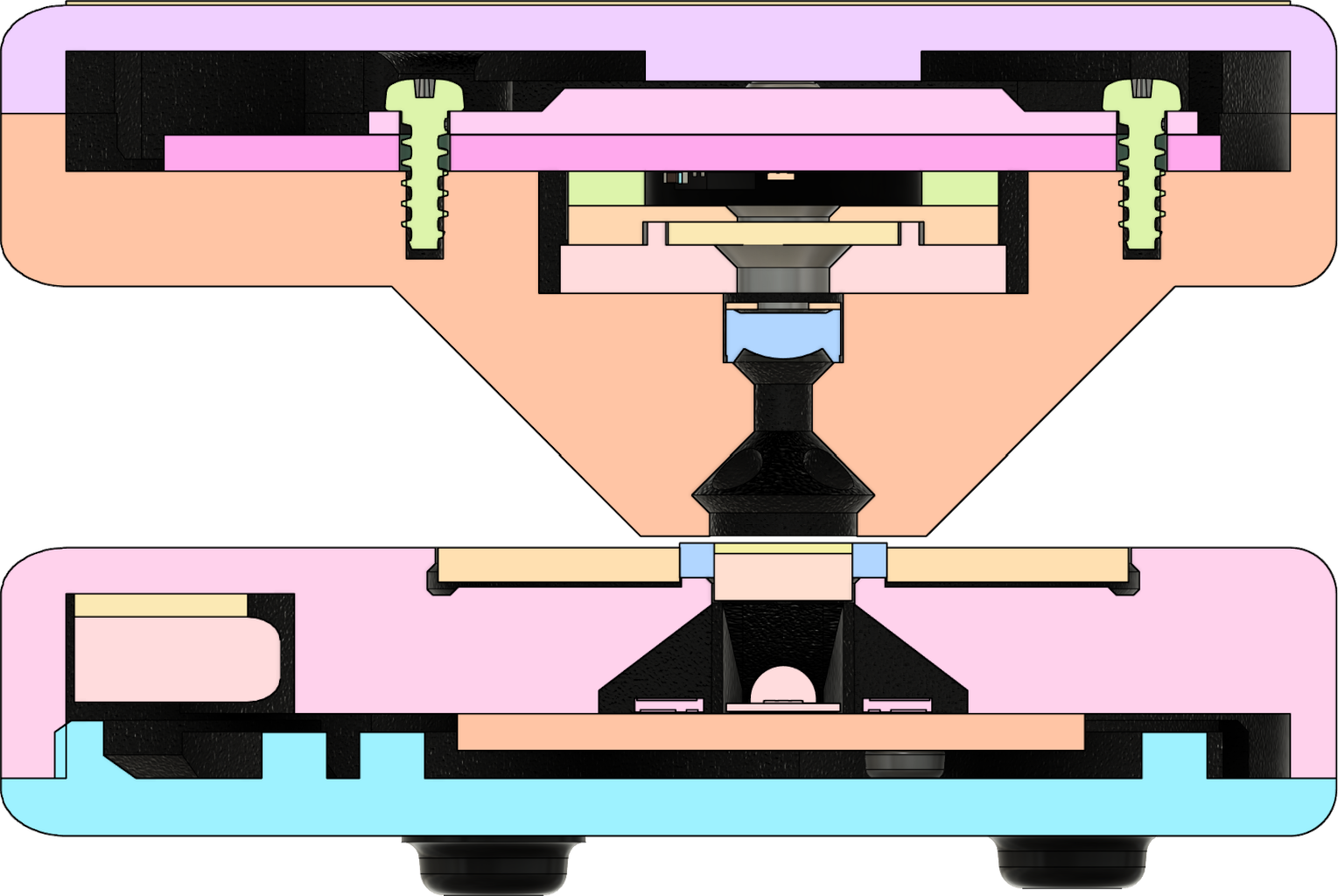

The sensor head is designed to support both reflection and transmission measurements from a single integrated light sensor, using multiple light sources. It is articulated using a hinge mechanism that brings the two halves of the unit to a repeatable alignment and parallel position, when an object no thicker than a normal piece of photographic film or paper is placed in-between.

For reflection measurements, the light source consists of four 3000K white light emitting diodes (LEDs) arranged and directed so that they shine at a 45° angle to the target. This arrangement was chosen to ensure even illumination regardless of surface or alignment imperfections, and because it provides a converging cross-hair effect when positioning a target to be measured. The LEDs are driven with a constant current that is matched between all four of them to ensure even illumination.

For transmission measurements, the light source consists of four 3000K white LEDs and a single 385nm UV LED positioned below a flashed opal diffuser in the base of the unit. This arrangement provides the same illumination effect as if both a white and a UV LED were occupying the same spot. The white LEDs are driven by a constant current driver that is matched between all for of them to ensure even illumination, while the UV LED has its own separate constant current driver.

The light path towards the sensor itself, within the sensor head, consists of a focusing lens followed by a fixed aperture and a UVFS diffuser. These help tighten the measurement spot, increase the amount of light that reaches the sensor, and even out the light hitting the surface of the sensor itself.

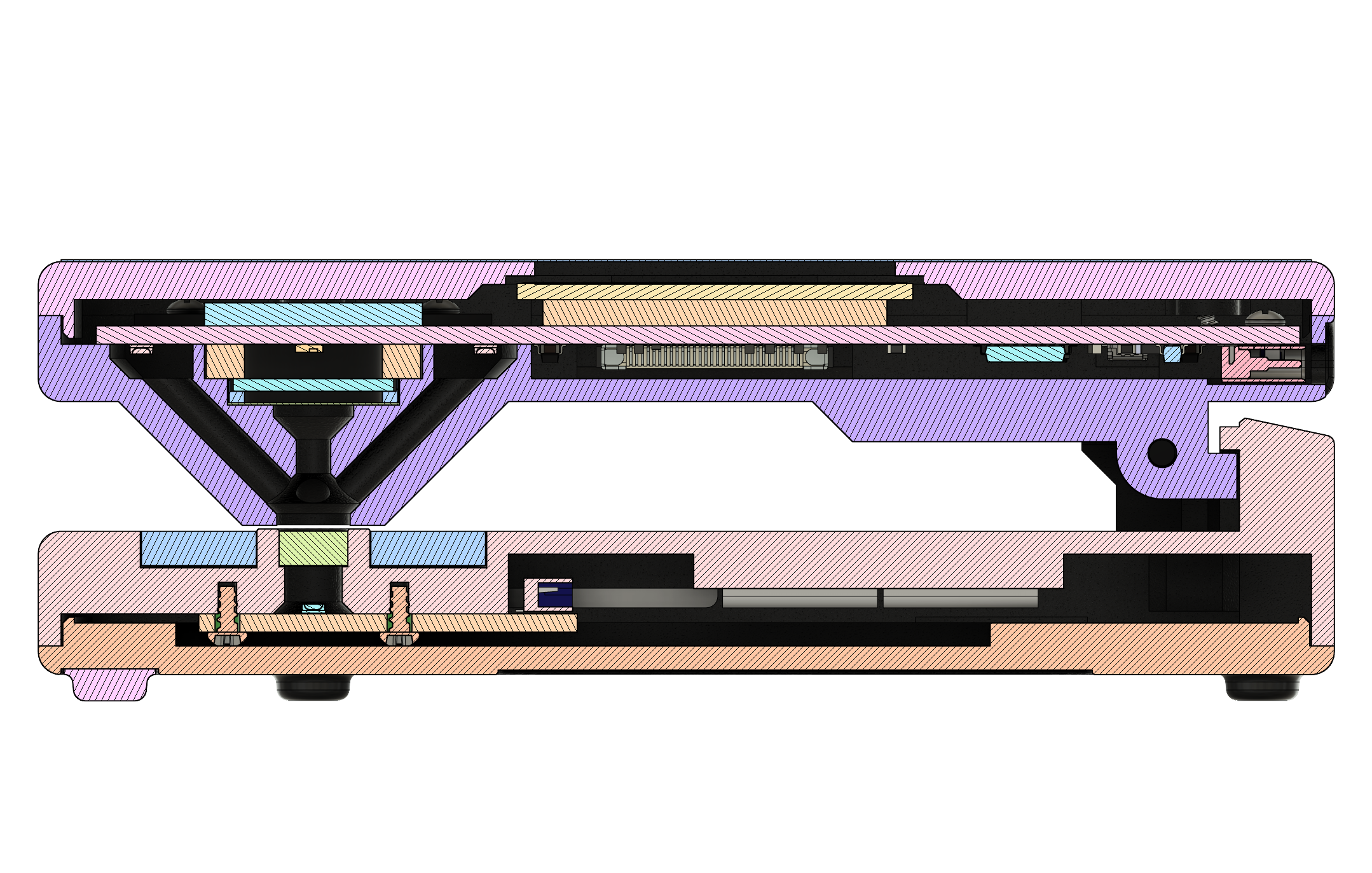

Fig. 11 Cross-section (side view)¶

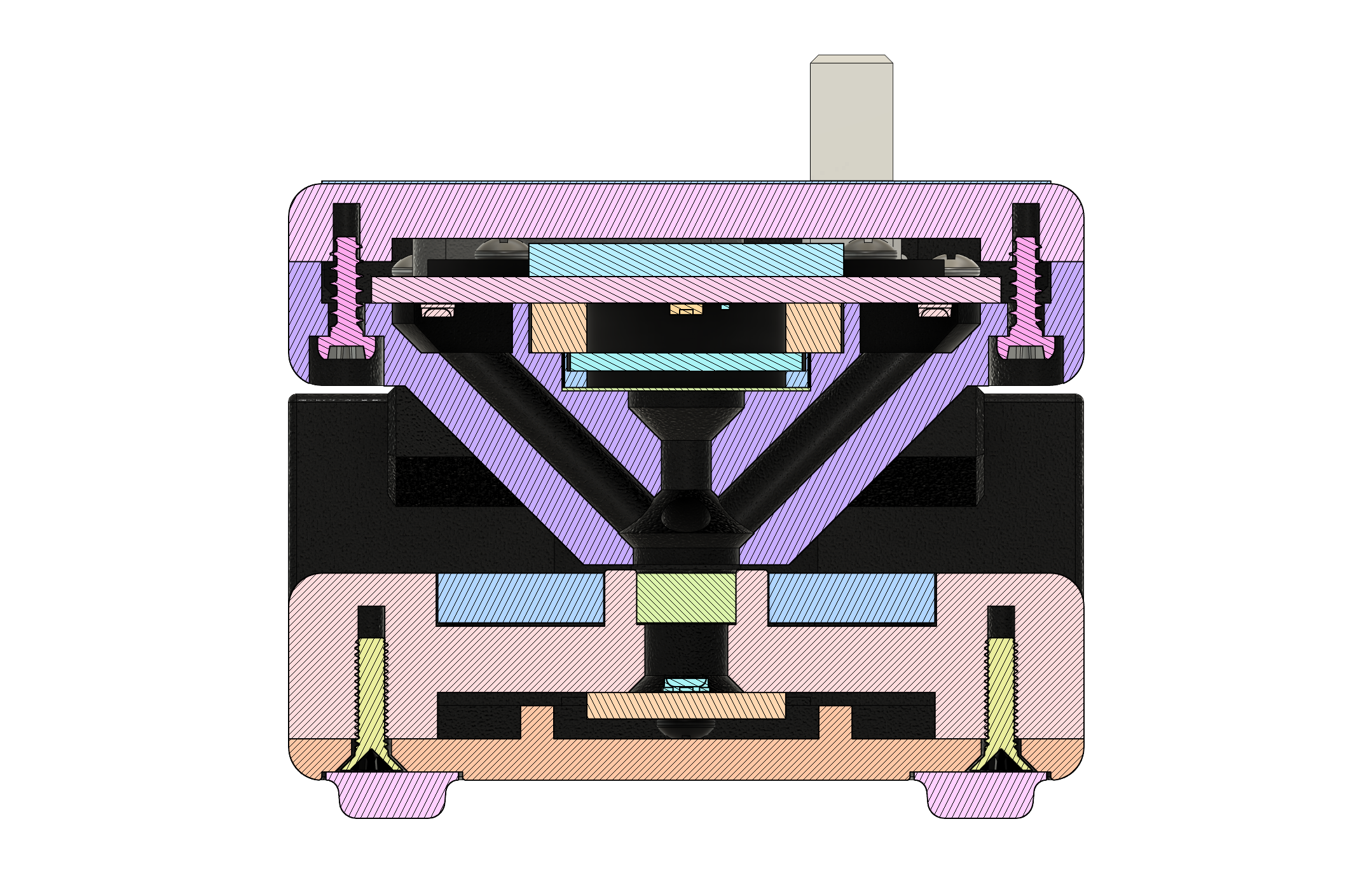

Fig. 12 Cross-section (sensor head)¶

Fig. 13 Cross-section (sensor head, 45° angle)¶

Response Spectrum¶

The response spectrum for visual density mode is based on “ISO 5 standard visual density” as described in ISO 5-3:2009. The spectral products for this density mode are officially based on a CIE standard illuminant A light source, and a sensor whose response spectrum matches the spectral luminous efficiency function for photopic vision (\(V_\lambda\)).

It is not practical to use a true CIE A light source in a compact modern device, as it is typically a tungsten-filament lamp with a color temperature of approximately 2856K. Instead, a LED-based source with a color temperature of approximately 3000K is used. This is not an exact match for the ISO 5 visual spectrum, but it does come quite close as can be seen in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14 Spectral response of the visual light source and sensor¶

The response spectrum for ultraviolet (UV) density is determined a bit differently. As there does not appear to be any standard for UV density, it is up to the manufacturer of each device to determine what works best for them. For this reason, comparing readings between different instruments may be difficult.

The Printalyzer UV/VIS Densitometer uses a sensor with a relatively flat response spectrum across the UV-A range, combined with a narrow 385nm (10nm half width) UV LED light source.

Footnotes